You have a scientific instrument that has never been tested in space. You need to experiment and tinker and calibrate to get everything just right. You must make sure your gear can survive the extremes of a launch and of orbit. You have managers with limited dollars to spend and a wise instinct to be cautious with them.

What do you do? You build a prototype and fly it on the Space Shuttle. Over three decades, the shuttle served as a critical testbed for remote sensing instruments that would eventually fly on satellites. In fact, many of the technologies in NASA’s Earth Observing System made their maiden flights in the back of NASA’s space pick-up truck.

Photograph of the Lidar In-space Technology Experiment aboard STS-64. (Astronaut Photograph STS064-72-093)

The poster child for instrument testing is the Lidar In-space Technology Experiment, or LITE, carried into space in September 1994 on shuttle Discovery. The goal was to see if laser detection and ranging, or lidar, could help scientists study clouds, pollutants, and airborne particles from the vantage of space. Lidar shoots a quick burst of laser light at a target and observes the reflection and scattering of the light, which varies with different types of particles. (Radar does the same thing with radio waves.)

Dust over the Sahara. (Astronaut Photograph STS049-92-71.)

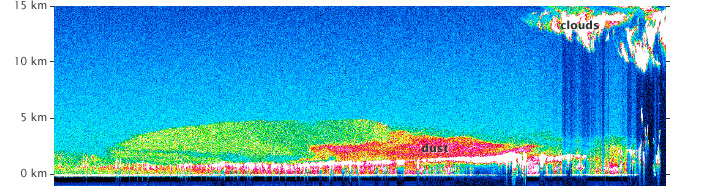

Could the instrument distinguish water clouds from dust storms, like the one spied by astronauts in May 1992 (above) over the Sahara Desert? Could it separate ice particles from volcanic ash, or pollution from forest fire smoke? Could it show the altitude of those floating particles?

Profile of dust above the Sahara Desert from the Lidar In-space Technology Experiment. (Image courtesy Aerosol Research Branch, NASA Langley Research Center.)

In 53 hours of testing over 11 days, LITE provided answers to all of those questions, giving atmospheric scientists their first detailed, global view of the vertical structure of clouds and aerosols from the middle stratosphere down to the Earth’s surface. It also found one of those Saharan dust storms, as shown in the data plot above.

More importantly, LITE paved the way for future space lidar missions, such as the Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite (ICESAT) and the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observation (CALIPSO).