A Dangerous Past |

|||

After the collapse, people speculated that something called a glacial surge had triggered the Kolka collapse. “In a surge,” explained Petrakov, “the leading edge of a glacier might slip a few hundred meters down slope very rapidly—perhaps in a day. A similar event happened at Kolka in 1969.” In 1902, a more significant collapse at Kolka Glacier had killed 32 people. Despite a history of disasters there, routine monitoring of the Kolka Glacier cirque ended shortly before the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. |

|||

It was the region’s dangerous past that drew Chernomorets, Petrakov, and Tutubalina to the area in September 2001, the year before the catastrophe. The three had enjoyed a camping trip to the region to see the site of the 1902 collapse, explore the glaciers, and enjoy the scenery. In the absence of regular scientific monitoring of the Kolka Glacier, the group’s observations during that trip were some of the most recent. |

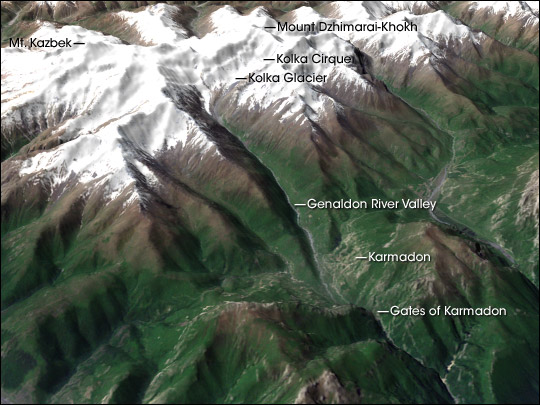

Large-scale avalanches and glacial collapses are not uncommon on the slopes of Mount Kazbek and nearby peaks. The Kolka Glacier collapsed in 1902, surged in 1969, and collapsed again in 2002. Evidence, including historical accounts, indicates similar events have happened in neighboring valleys, as well. (NASA Image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon based on MODIS data) | ||

| |||

“We arrived in Karmadon in the evening of September 21. It was getting dark, and we could barely see the valley slopes,” Tutubalina says. “We remember discussing: ‘Well, although hill-walking rules do not recommend camping near mountain rivers, the sky is clear, and at the end of September, debris flows from the slopes are unlikely, so we should be all right.’” They camped right by the Genaldon River. The same decision a year later would have cost them their lives. |

Ice from the Kolka Glacier filled the bottom of the Genaldon River Valley and spread across a portion of the Karmadon Depression before slamming into the Gates of Karmadon and coming to a halt in a pile of dirty ice 130 meters (390 feet) high. This perspective view shows the topography of the region. (NASA image by Robert Simmon based on SRTM and Landsat-7 data provided by the Global Land Cover Facility) | ||

Getting to KolkaIn the days following the disaster, survivors were demoralized and afraid of what might happen next. Petrakov, Chernomorets, and Tutubalina felt they had to help calm people’s fears if they could, or help them prepare for any further disaster if they could not. “The disaster happened on Friday night, about 8 p.m., and the news of it didn’t reach Moscow until the next morning,” recalls Tutubalina. “Sergey and I were taking a stroll in a national park some 50 kilometers west of Moscow, when Dmitry rang Sergey’s mobile [phone], and told us the news he’d just seen on the Internet. We wanted to fly to the area with the rapid response team of the Russian Emercom [Russian Emergencies Ministry] because we had specialist knowledge to assess the situation. When we got back to Moscow in the evening, Sergey started calling the Emercom people, but by the time we got in touch, it was too late to join the plane.” They spent the next 10 days following the situation through mass media and Emercom reports, while struggling to find funding for their own expedition. When promised funding fell through again and again, they gave up and used their own money. “This was a unique event of a planetary scale,” Tutubalina explains. “We felt we could make a significant contribution to the study of the scale of the disaster and the remaining danger, as we knew what the area looked like one year earlier.” Because the glacier had not been routinely monitored in more than a decade, the team’s 2001 sightseeing observations were some of the most recent. |

During a trip in 2001, exactly one year before the Kolka collapsed, Olga Tutubalina and her colleagues camped dangerously close to the Genaldon River. In this photograph, Tutubalina cooks lunch near the Genaldon (left) just a few kilometers away from Kolka Glacier. (Photograph courtesy Sergey Chernomorets) | ||

The decision to fund the trip out of their pockets ruled out any helicopter support to transport heavy scientific equipment. They could only take equipment they could fit and carry in their backpacks along with their camping gear and food. They stuffed their packs with GPS units for mapping the precise location of important geologic and glaciological reference points, simple geodetic equipment for measuring angles and topography, and digital and photographic cameras. Thanks to colleagues from the Caucasus region—Eduard Zaporozchenko and Alexander Polkvoy—they were able to reach Karmadon despite the fact that local transport had stopped after the disaster. |

Dmitry Petrakov (second on right) and his colleagues Anastasia Rozova, Victor Popovnin, and Eduard Zaporozhchenko rushed to Karmadon in early October 2002 to determine the cause of the collapse and assess the risk of subsequent avalanches or catastrophic flooding. (Photograph courtesy Sergey Chernomorets) | ||